御盆 Obon in Okinawa is often referred to as “kyuubon” 旧盆, which means “old Bon” because it is celebrated according to the lunar calendar (7th lunar month, 13th through 15th days 旧暦7月13日-15日). Some other areas in Japan celebrate it either in July or August 13-15th. It is also called “Shichiguachi” しちぐぁち, meaning 7th month in Okinawan language. It should also be noted that different areas of the Ryukyu islands actually have their own names and traditions for Obon (for instance, Ishigaki-jima and the Yaeyama islands have something interesting called “Angama”); the ones I write about are the most common for Okinawa main island. Many Obon traditions and customs observed in Okinawa are quite different from the ones typically seen on mainland Japan. Something important to note: the Japanese custom of toro nagashi 灯籠流し is not a common practice in Okinawa, so you will not see candle-lit lanterns released afloat on the water during Obon like you might in parts of mainland Japan.

Obon is a custom to commemorate one’s ancestors; the spirits return to this world for 3 days to visit family. It is sometimes referred to as “ghost festival,” “lantern festival,” or “festival of souls” in English.

In 2018, Obon will be on Aug 23-25th and Tanabata will be Aug 17th.

There are 3 days of Obon in Okinawa:

ウンケー unke/unkeh (お迎え): 1st day, welcoming day, when the sun sets. This is the day where families usually visit graves and welcome the ancestors home. Families will gather at the eldest son’s residence (where the family altar, a butsudan 仏壇, is kept). The family altar is set up, and offerings of fruit, mochi, sweets, sake/awamori, beer, and stalks of sugarcane are placed. The sugarcane is left as walking sticks for the spirits walking from the heavens. Obviously the ancestors favorite foods are also usually placed. Lanterns are set up to guide ancestors home.

ナカビ or ナカヌヒ nakabi or nakanuhi (中日): 2nd day, the middle day. On this evening, all my neighbors leave their doors and windows open, and have a large family dinner. The doors and windows are open to allow the ancestors to enter the home. Also, I see a lot of people distributing “gifts” (known as 御中元 ochuugen) on this day (mostly these are random food and household item gift sets sold in department and grocery stores all over), but any day leading up to or during Obon seems to be okay for distributing summer gifts. The eldest son’s family is in charge of the altar, so they must stay at home to receive other family members and visitors; so while the eldest son’s wife has to prepare many foods and the altar for Obon, they also receive many “gifts” in return, usually in the form of rice, beer, laundry soap, etc. For those family that are not the eldest child, instead they must prepare gifts and visit everyone else’s home where the altars are kept. So either way, it is sort of an expensive endeavor.

ウークイ uukui/ukui (御送り or 精霊送り): 3rd day, farewell day. This last day of Obon is filled with music and eisa (Okinawan bon dance), to say farewell to the ancestor spirits and escort them back to the heavens. There is usually a big feast late into the night, with various foods that are offered and special paper money called uchikabi ウチカビ is burned as for the ancestors so that they can use it in the spirit world. Some offerings and sugar cane is left out by the gate/fence/side of the road for the spirits to take home. This day, on the hillside by my village, you can see a large kanji lit up (they use electric lights, not actually burning into a mountain like Japanese tradition). Maybe this year I can get a decent picture of it; it represents some sort of farewell to the dead.

Before Obon, is Tanabata 七夕. In Okinawa, rather than celebrate star festival, it is more common that this is a grave-cleaning day to prepare for Obon and to ask ancestors to come visit during Obon season. It is believed that the ancestors protect their descendants in the real world, so it is important to take of them in their afterlife.

For the butsudan 仏壇 (altar) set up, many things are included. I will explain what is common in Okinawa… probably places in the mainland are a bit different, though some things will be the same or similar.

rakugan 落雁: this is dried “sweets” pressed into a mold (very water soluble so it lasts a long time). Despite the colorful appearance, the taste is very subtle, just a little sugar; since this is for altar offerings it is usually more “starchy” than sugary (made from mizuame 水飴, a glutinous rice starch syrup). These tend to be dry and a bit starchy-sweet in flavor. It is a type of Japanese confection (wagashi 和菓子) called higashi 干菓子, which is dried and has low moisture content. Often these will also be called bongashi 盆菓子 (Obon sweets) or kyo-kashi 供菓子 (or お供え菓子).

sugarcane, uuji ウージ (さとうきび satou kibi in Japanese): set out as walking sticks for the spirits. It can also be used to help ancestors carry souvenirs back to the spirit world. There are 2 types set out: long, guusanuuji グーサンウージ to use as a walking stick and as a balancing pole to carry souvenirs, and short, chitu uuji チトゥウージ also used to help carry back souvenirs. Sometimes the short sugarcane is also used as minnuku ミンヌク (水の子 in Japanese, set out as small offerings to Buddhist gods or to keep out bad spirits).

medohagi メドハギ or soromeshi ソーローメーシ (精霊箸): a type of weedy plant. Chopsticks for the ancestors use. I also read somewhere that this can be set out for purification purposes as well.

ganshina ガンシナー: circular ropes so your ancestors can take souvenirs (foods) back to the spirit world; they are used to balance foods or gifts on your head. On the altar they are typically displayed by balancing watermelon, pineapple, oranges, etc. on them.

ukui kasa ウークイカーサ: Alocasia leaves. This is apparently used so your ancestors can wrap souvenirs to take back to the heavens.

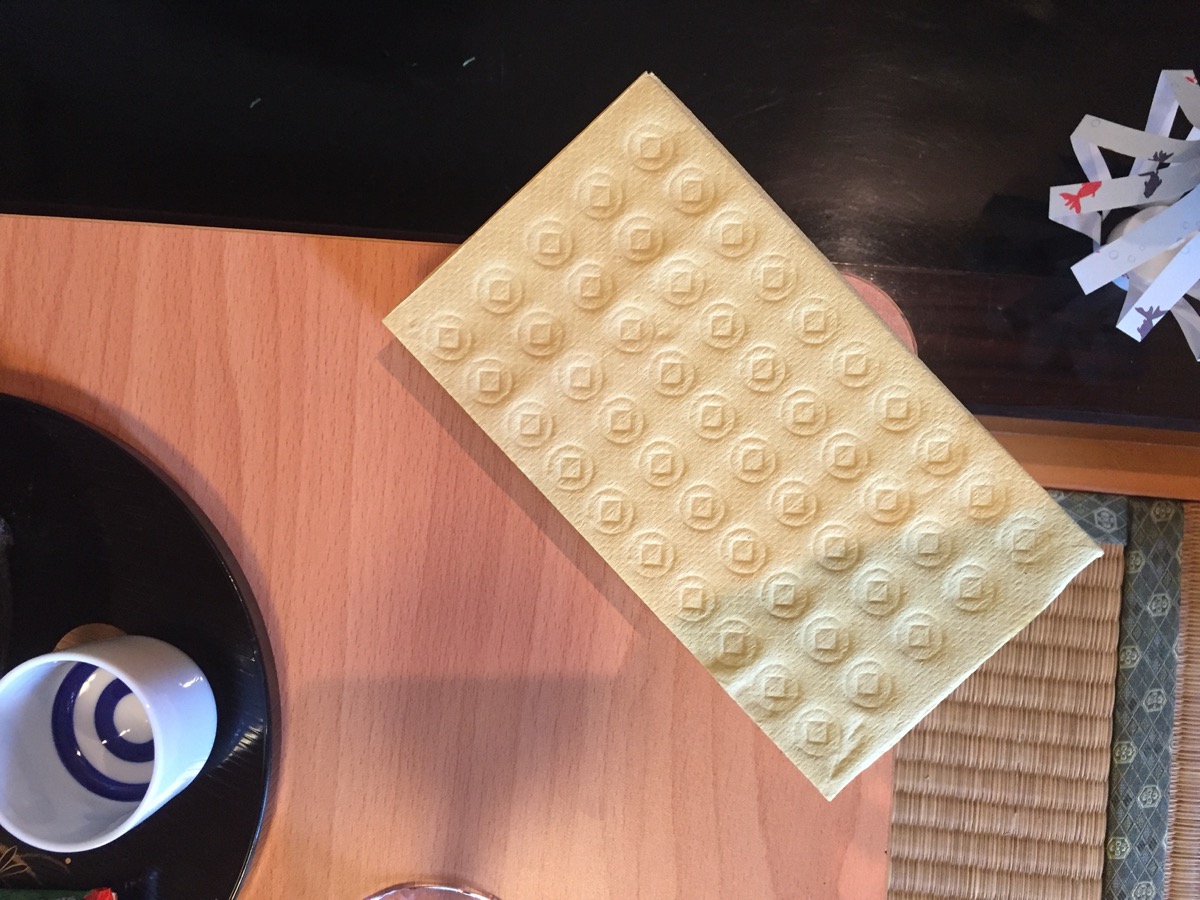

uchikabi ウチカビ (打紙): Afterlife money! It is a Japanese paper with the design of coins on it. It is burnt on the last day (ukui) so that your ancestors have money in the afterlife.

eggplant cow (nasu no ushi ナスの牛) & cucumber horse (kyuuri no uma キュウリの馬): placed outside the home so the ancestors can ride on them from the spirit world home, then placed on the altar on the first day of Obon. This is actually more of a mainland thing than Okinawa, instead here uses the sugarcane since it seems Okinawa ancestors come on foot. In Okinawa, you may even see a variation using a goya ゴーヤー. With them is placed mizunoko 水の子, washed rice with diced cucumber and eggplant; although this is optional, it is supposed refresh returning spirits after their journey.

somen そうめん: somen (noodles) are usually place on the altar as well. I don’t know why exactly, but the theory seems to be because somen is easily used in summer cooking, so it is convenient. I also hear it is to use as reins for the ancestors to ride the animals back to the spirit world.

houzuki ほうずき, ホオズキ, or 鬼灯: Chinese lantern plant. It helps light the way for ancestors. These are really quite pretty, and really do look like tiny red lanterns.

senkou 線香 (ukou ウコウ in Okinawan): incense sticks (for purification). Often in Okinawa flat incense is used, called hiraukou ヒラウコウ (平線香).

bon-chouchin 盆提灯: lanterns; these are placed at the altar and the front of the house, so spirits don’t lose their way.

makomo まこも: mat woven from straw of wild rice, used in rituals.

Of course, flowers, seasonal fruits/vegetables, and your ancestors favorite foods (and drinks, usually beer or awamori) are also included on the altar. Typically UNRIPE fruit is used since it sits on the altar for 3 days… so sometimes it is not always so good to eat raw, but instead cooked. Also keep this in mind if you are fruit shopping at the markets during Obon, since many of these fruits will not ripen properly because they are picked so early! Look for signs that indicate 供え物 or 供え用 (translation: for offering/altar use); as well as signs like 青切り (translation: fruit picked early before becoming ripe) and 生食用ではありません (translation: do not eat raw). The 2 you must be MOST careful of are: sticks of sugarcane (it is not for eating and will not be tasty) and pineapple (can only be eaten cooked, do not eat raw). The bananas should be able to ripen somewhat but are also delicious cooked. Mikan (oranges) will be very sour, so maybe this is okay for some people. Unfortunately for many foreigners, the signs are always in Japanese explaining these things!

Below is a sweets offering set for the altar (お供え: offering, 菓子: sweets), easy to find in the grocery stores; unlike rakugan described above, these are in fact very tasty.

On unkeh, there is the custom of eating unkeh juushii ウンケージューシー, which is a type of Okinawa cooked rice with various things mixed into it. It is a simple, but popular dish.

There is usually a box of specific foods during the feast day (ukui) called “usanmi” 御三味 (ウサンミ) that contains: fried tofu 揚げ豆腐, burdock root (gobou ごぼう), kelp (usually tied in knots), fish cake (kamaboko かまぼこ), konnyaku こんにゃく, tempura 天ぷら, fried taro (田芋 taimo) and of course, pork. There also usually a second box of white mochi (rice cakes) set out as well.

Not on the altar, but commonly served for during Obon are your typical trays of sushi, sashimi, fried things, chilled zenzai (sweetened red beans and mochi), cold somen noodles, nakami-jiru 中味汁 (intestines soup).

The local grocery stores in Okinawa have ads for all your Obon needs… this is an example of an advertisement from SanA. Anymore, many people just order trays of オードブル (pronounced ohh-do-bu-ru), which comes from the word hors d’oeuvres, instead of making it all themselves.

While most “events” are private in peoples homes, there are a few goings on, mostly in the form of eisa dance. Traveling groups of eisa often visit various spots throughout the community; by our house, one group comes to the FamilyMart and performs for a nice little show before moving on to the next location. If you live near Okinawa city and the middle part of the island, eisa typically goes on for all 3 nights of Obon, and sometimes another night after that, so be prepared for the continuous sounds of drums and sanshin (click here for Where to see eisa during Obon…). Another fun/interesting event is the Miruku-kami ミルク神 “parade” in Shuri.

I often walk through my neighborhood in the evenings; during obon time, all the doors and windows are left open to the houses. Drums and eisa dance chants ring through the air. I see neighbors burning or wrapping up offerings and leaving them outside on the walkways. It is somehow a nostalgic summer feeling.

In addition, people do not go into the sea during Obon, lest they be dragged to the underworld by deceased souls in the water (typically those who died by drowning or water accidents).

Hello! Thank you for your in-depth post about kyuubon!